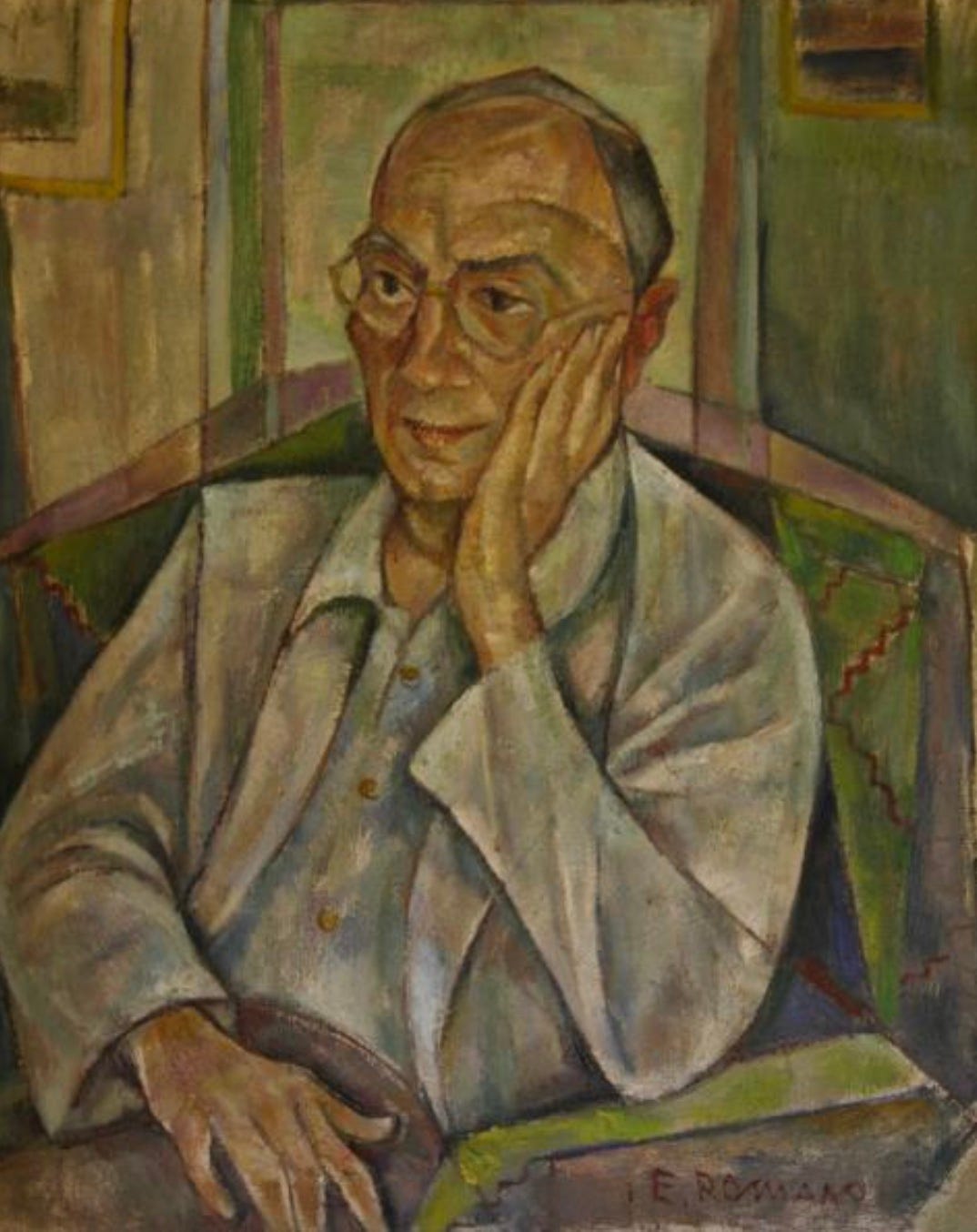

A Poet Learns to Read

With young Denise Levertov's help, William Carlos Williams could read again

On a chilly morning in early December 1953, the aging physician and poet William Carlos Williams sat stiffly before an oaken table in a 5th floor office at 235 East 46th Street in Turtle Bay, Manhattan. He’s there at the suggestion of a new friend, young poet Denise Levertov, who not long before had sought Williams out hoping to learn from an elder writer she admired.

Two strokes had left Williams, then sixty-nine years old, with what he described to Levertov as “the condition of my eyes, maybe it would be more exact to say the condition of my reading.” His inability to read as he once did was not unlike deaf Beethoven’s suffering. Famously, while Beethoven was able to compose his Ninth Symphony he was unable to conduct its premier because he couldn’t hear it. Similarly, Williams could still compose his poetry but he had difficulty reading it or anything else.

Levertov and Williams became close friends in a short amount of time and she was happy to help him after his strokes. She would often read to him, and she searched New York for a place Williams could go for help with his reading. She found the Yoder Reading Improvement Center on East 46th, which was run by the energetic and colorful Hilda Yoder.

Since first reading of this in the published letters between Williams and Levertov, I’ve tried often to imagine the scene: the distinguished poet, winner of the National Book Award the year before, sitting nervously if hopefully with a reading therapist on a gray December day in New York. Could she help return him to his beloved river of literature?

Maybe Yoder tried to help him relax with a light-hearted tale of her comeuppance happening over the very days she began treating Williams. She’d been quoted by the nationally syndicated columnist Earl Wilson regarding her recent trip to her birthplace in Hickory, Catawba County, North Carolina. She’d told the columnist that she was a “barefoot hillbilly from Hickory,” adding, "When I went to the Catawba celebration I didn't know whether to show up with my shoes on or off." To this the home folks took great exception to the insult to their “shoefulness,” as one local put it. The Daily Tarheel newspaper reported that “the people of Hickory and Catawba want the world to know that they are not hillbillies and that they ‘do wear shoes when they leave their home grounds.’"

Hearing the story, Williams might have joked, “It is a tale of the variable foot,” punning on his famous term for the poetic line length he invented.

He and Yoder appear to have worked well together. In a letter to Levertov, Williams wrote, “You have found out exactly what I want to know; the Reading Improvement Center on E.46 seems made to order and if after a few private instruction sessions I can go it under my own steam so much the better.”

A few days later in December, Williams’ wife Florence wrote to Levertov thanking her. “Dear Denise—You have been most helpful in rooting about for the proper place for Bill to go—and he is now attending the Reading Improvement Center and feels encouraged—after only two sessions! Thanks to you.” At the end of January, 1954, Williams was able to perform a public reading of his poetry at the 92nd Street Y in New York. Helen Yoder attended the reading.

So did Levertov. She wrote to her parents saying, “It was a triumph—he was absolutely marvellous. I was so happy to think I had had something to do with the improvement in his reading.” I was unable to access a recording of Williams’ performance that night, but there are recordings he made at home in June of 1954. He doesn’t sound at all like a man who had trouble reading just a few weeks earlier.

I couldn’t find any details about Yoder’s therapy. Levertov wrote that Yoder taught Williams to rest for a moment if he made a mistake. The 1949 annual report of the Presbyterian Hospital of New York, where Yoder also worked, noted positive results from her teaching of “physical relaxation among poor readers.”

That’s not much to go on, though I could point out that in St. Benedict’s 5th Century rules for monks, his Lectio Divina or Sacred Reading rules also include advice to rest. A different context, I know, and only a small portion of Benedict’s instructions, but still. Who hasn’t read better by slowing down and resting until the reading is clear?

Some years later as his health continued to fail, Williams’ reading troubles worsened. Levertov, in a 1997 note filed with her correspondence, wrote of the “later trouble he had when though he cd. see the words, optically, he could not translate them into meanings & sounds.”

In 1957 Williams sent Levertov a broadsheet of his translation of Sappho’s Fragment 32. Early on he’d mentioned Sappho to Levertov when discussing one of her poems. Now he wrote to her that he “was satisfied that some of the classic translations I have seen were horrible then made my own transliteration.” His reading abilities were good enough that he could be “veritably shocked by the official British translations of a marvelous poem by one of the greatest poets of all time,” as he later wrote.

After receiving the Sappho translation, Levertov wrote back, “How lovely – your poem, the Sappho. Thank you very very much. I tacked it up where it gives lustre to all around it & great joy to me.”

Many years ago I was lucky enough to come across #48 of a limited edition of 150 of the Sappho broadsheet signed and numbered by Williams. It’s still hanging on my wall where it also gives great joy to me.

Postscript: Levertov added a P.S. to her letter thanking Williams for the Sappho: “Did you know you wrapped the poem in a Law Degree [his honorary degree from the University of Buffalo]?”

Williams wrote back, “Please return the case containing the law degree, I don’t see so good sometimes.”

Here is Williams’ Sappho, Fragment 32. His post-stroke difficulties are apparent in his signature:

Well, gap year has concluded. Get back to work.

This is wonderful stuff, Mr. Smith. You've been away too long.